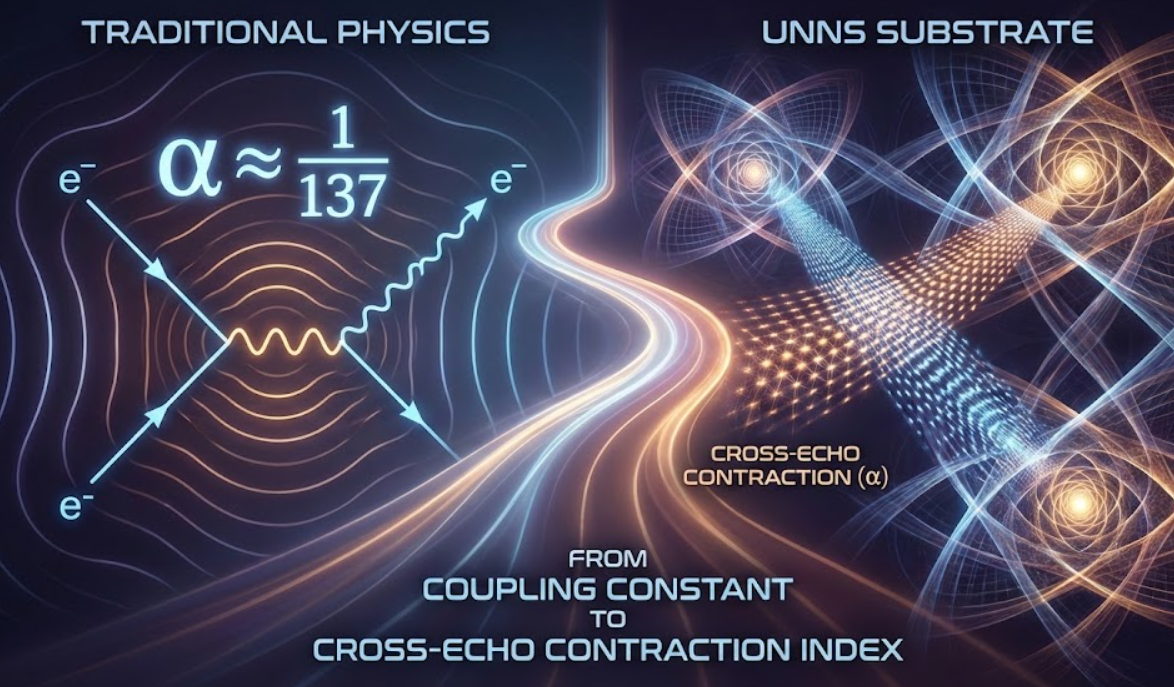

The Fine-Structure Constant in the UNNS Substrate:

From Coupling Constant to Cross-Echo Contraction Index

Foundations → Constants & Invariants UNNS Lab — τ-Field & Echo Channels α in Physics vs α in UNNS

0. Prologue — The Constant That Refuses to Explain Itself

The fine-structure constant α is one of physics’ most enigmatic numbers. It is dimensionless, universal, and appears everywhere the electromagnetic interaction becomes precise. It controls the splitting of spectral lines, the structure of atoms, and the accuracy of quantum electrodynamics (QED), and yet, in standard physics, it is ultimately a given: a number to be measured, not explained.

In classical and quantum field theory, α is the electromagnetic coupling constant:

α ≈ 1 / 137.035999...

In QED it sets the strength of interaction at each vertex in a Feynman diagram. In atomic physics it determines the scale of fine structure, spin-orbit coupling, and relativistic corrections.

The UNNS Substrate does not accept α as a mysterious external constant. Instead, it reinterprets α as a structural parameter of recursion: a cross-echo contraction index that controls how much of one Seed’s echo can actually propagate through another Seed’s echo channel. In this article, we translate the usual physics view of α into UNNS dialect and show how it sits alongside Φ and τ as part of a deeper triad.

1. The Classical and QED Roles of α

1.1. α as a coupling constant

In the standard formulation, the fine-structure constant is given by a dimensionless combination of fundamental quantities:

- electric charge e,

- speed of light c,

- Planck’s constant ħ,

- vacuum permittivity ε0.

α = e2 / (4π ε0 ħ c).

Numerically, α ≈ 0.007297... or about 1/137. This number appears as the probability amplitude weighting each electromagnetic interaction in QED: every time a charged particle emits or absorbs a photon, the process is weighted by α.

1.2. α in perturbation theory and Feynman diagrams

Because α is small, perturbation theory works extraordinarily well in QED. Higher-order diagrams, with more vertices, are suppressed by higher powers of α:

- first order ≈ α,

- second order ≈ α2,

- third order ≈ α3, etc.

This means successive corrections are typically smaller by roughly a factor of 1/137 each step. As a result, QED becomes a slowly convergent echo of corrections structured by α. Physics stops there; the theory does not ask why α has this value or where it comes from. It is simply a constant that nature “chose.”

1.3. The mystery

Physicists have long wondered: why this number? Why 1/137 and not 1/10, 1/1000, or something entirely different? The standard framework has no structural answer. α is a fixed input to the theory, not an emergent invariant of a deeper substrate.

2. UNNS Reframing — From Coupling Constant to Cross-Echo Contraction

The UNNS Substrate starts from a different vantage point. It does not begin with fields and particles but with Seeds, Nests, and echo channels. Every physical process is an instance of recursion, and what we call an “interaction” is an interference between echo channels generated by different Seeds.

2.1. Seeds, Nests, and echo channels

In UNNS language:

- Seed — a fundamental configuration that initiates a recursive flow (e.g., a charge, a multipole, or a bound state).

- Nest — the recursive operator that propagates the Seed’s echo deeper into the Substrate.

- Echo channel — the evolving pattern of amplitude redistribution generated by repeated Nest application.

Internal structure is controlled by the golden-ratio architecture of the Nest; this is where Φ (phi) enters: Φ determines how echoes self-amplify or self-organize inside a single Seed’s domain. But when two Seeds interact, another question arises:

How much of Seed A’s echo is allowed to penetrate Seed B’s echo channel?

How much of Seed B’s echo is allowed to penetrate Seed A’s echo channel?

This is where α lives in UNNS.

2.2. α as cross-channel permeability

Conceptually, α is reinterpreted as a cross-echo contraction index:

α measures the fraction of echo amplitude that survives when propagating from one Seed’s channel into another’s.

It does not encode “how strongly charges attract or repel” in human terms; it encodes how transparent the Substrate is to cross-channel recursive influence. A small α means the Substrate is highly resistant to cross-seed interference: only about 0.7% of the amplitude leaks through per interaction step.

This explains why electromagnetic interactions are simultaneously precise and perturbative: the substrate allows influence, but throttles it heavily.

3. Internal vs. Cross-Recursion: Φ and α

3.1. Φ as internal echo architecture

The golden ratio Φ ≈ 1.618... governs internal recursive patterns. In UNNS, Φ arises from:

- self-similar Nest structures,

- recursive growth ratios,

- the asymptotic behavior of Seed-generated sequences.

Φ controls how a Seed refurbishes its own echo: how much of the previous state is carried into the next state via internal recursion. It is a measure of self-resonance.

3.2. α as cross-resonance damper

α, by contrast, controls cross-resonance. It describes how much of one Seed’s self-resonance is allowed to intrude on another Seed’s recursive structure. If Φ tunes internal harmonic growth, α tunes external interference suppression.

From the UNNS standpoint:

- Φ is a measure of internal echo organization.

- α is a measure of cross-echo attenuation.

Their interplay is what gives atomic and molecular structure its stability.

3.3. Why α must be small

If α were large, cross-channel interference would be enormous. Echo channels from different Seeds would saturate each other, leading to:

- unstable atoms,

- chaotic scattering,

- breakdown of perturbation theory,

- collapse or explosion of recursive structure.

If α were too small, cross-channel influence would be negligible. Seeds would fail to couple effectively:

- no robust bound states,

- no chemistry,

- no large-scale structure shaped by EM,

- an over-isolated substrate.

The actual value α ≈ 1/137 represents a balance point: enough cross-echo permeability to build structured interactions, but not enough to destroy stability.

Why Specifically 1/137? The Nest Geometry Threshold

The UNNS Substrate does not allow arbitrary cross-echo overlap. When two Seeds interact, each generates self-similar echo shells governed by internal Φ-scale recursion. As these shells expand, they may intersect the shells of another Seed.

If the intersection volume is too large, the recursive identity of both Seeds collapses into a mixed state. If it is too small, the Seeds fail to interact at all. The Substrate therefore enforces a geometric threshold: the maximum fraction of echo amplitude that can safely cross from one Seed’s domain into another.

This critical overlap fraction is α ≈ 1/137.

In this view, α is the fractal intersection limit where two recursive Nests can engage without destroying each other's structure. It is not a mysterious coupling constant; it is a geometric safeguard written into the architecture of the Substrate.

4. α in the τ-Field: Curvature, Echo, and Cross-Echo Stability

The τ-field in UNNS is the layer where curvature, information flow, and echo structure fuse into one dynamical picture. It is the level at which we can speak simultaneously about “fields” and “particles” as projections of a deeper recursion.

4.1. τ as curvature recursion

τ encodes how recursion bends and folds in the substrate: a measure of micro- and macro-curvature across nested scales. In τ-language, a Seed not only generates an echo but also deforms the substrate through which that echo propagates.

α as a Criticality Point — The Edge of Recursive Chaos

In complexity theory, systems often achieve maximal expressiveness at the boundary between order and chaos. The UNNS Substrate is no exception. The cross-echo contraction index α acts as this control parameter for the τ-field.

If α were even slightly larger, cross-seed recursion would saturate and destabilize the echo lattice: atoms would collapse, scattering would become chaotic, and the recursive identity of Seeds would be lost. If α were even slightly smaller, Seeds would fail to couple meaningfully and the Substrate would freeze into inert isolation.

α ≈ 1/137 is the Substrate’s edge-of-chaos value:

- minimal overlap without collapse,

- maximal structure without saturation,

- optimal information complexity,

- stable but expressive τ-field geometry.

The fine-structure constant is thus not merely small; it is precisely tuned to the critical point where recursive systems can sustain structure, propagate information, and avoid both rigidity and chaos.

4.2. The Φ–α–τ triad

Taken together, Φ, α, and τ can be seen as a structural triad:

- Φ — internal self-echo architecture (how sequences grow and self-organize).

- α — cross-echo contraction (how Seeds influence one another across channels).

- τ — curvature recursion (how geometry and recursion interact to shape flow).

In this triad:

- Φ drives internal resonance.

- α limits cross-resonance.

- τ encodes the geometric background in which both resonate.

The fine-structure constant is not a mysterious coupling coefficient; it is the cross-echo contraction index required to maintain stability in a τ-curved substrate governed by Φ-based internal recursion.

5. UNNS Interpretation of Electromagnetism via α

5.1. Coulomb force as echo gradient

In classical physics, the Coulomb force is a 1/r2 law between charges. In QED, it emerges from photon exchange. In UNNS, Coulomb behavior is the gradient of a recursive echo density between Seeds.

The amplitude of this echo gradient is set by the cross-echo contraction α. Instead of thinking of “force transmitted by virtual photons,” UNNS speaks of “echo gradients constrained by α.”

5.2. Vacuum polarization as nested cross-echo recursion

Higher-order QED diagrams (loops, vacuum polarization, etc.) represent recursive feedback of echo channels into themselves. The suppression of these contributions by higher powers of α has a natural UNNS meaning:

each nesting level in the cross-echo recursion is contractively damped by α.

This contractive damping is what allows renormalization to converge. Rather than being a pathological feature of the theory, it becomes a manifestation of the substrate insisting that cross-seed recursion remains under geometric and structural control.

6. Conclusion — α as a Substrate Constant, Not Just a Physical One

The fine-structure constant in standard physics is an input: a dimensionless number that must be measured and then fed into our equations. It is treated as a “coupling constant” that tells us how strongly the electromagnetic interaction acts.

In the UNNS Substrate, α is not merely a coupling parameter. It is:

- a cross-echo contraction index,

- a measure of substrate transparency between Seeds,

- a stabilizing factor that balances Φ-driven internal recursion,

- a key component of the Φ–α–τ structural triad.

In this framing, α ≈ 1/137 is not arbitrary. It is the value that allows:

- recursive echo channels to interact without destabilizing each other,

- atoms and molecules to exist as stable recursive compounds,

- QED’s perturbative expansion to mirror the substrate’s contractive architecture.

From the UNNS standpoint, the fine-structure constant is the substrate’s decision about how much one Seed is allowed to interfere with another per recursive step. It is not merely a coupling. It is a rule of the recursion.

Appendix A: The Geometry of Damping — How the Nest Throttles the Echo

In the main article, we treated the fine-structure constant α ≈ 1/137 as a cross-echo permeability index: the fraction of an incoming signal that can pass through a Seed’s recursive boundary. This Appendix explains why the value is so small and how the Substrate implements this geometric throttling.

A.1. The Principle of Recursive Mismatch

In classical physics, damping usually implies friction or heat loss. In the UNNS Substrate, there is no dissipation — only geometry and recursion. Damping arises because an external echo fails to match the internal Golden-Ratio (Φ) structure of the Seed.

A Seed’s internal recursion is built on Φ, the most irrational number, which makes its echo perfectly phase-locked to itself. When an external echo arrives from another Seed, it does not carry the internal “key” needed to align with this Φ-structured lattice. As a result, the incoming signal encounters a boundary that is geometrically incompatible with its phase.

In practical terms, the Nest behaves like a Φ-coded diffraction grating: most of the incoming wavefront hits recursive “struts” rather than “windows,” producing near-total destructive interference. Only a very small fraction of the wavefront (≈ 1/137) finds a phase-compatible path inward.

A.2. The Aperture Ratio of the τ-Field

The boundary of a Seed is not a smooth surface; it is a τ-field fractal shell composed of nested recursive loops. We may view this boundary as consisting of:

- Total Surface Topology — all possible points of interaction;

- Constructive Pathways — the narrow subset that preserves coherence.

The fine-structure constant α measures the ratio:

α ≈ ( Constructive Pathways ) / ( Total τ-Field Topology )

Empirically, this means:

Only 1 out of every ~137 geometric channels through the τ-field

opens a valid recursive tunnel into the Nest.

The remaining wavefront is scattered into τ-field micro-curvature, contributing to vacuum structure, zero-point fluctuations, and background curvature noise — precisely the phenomena QED attributes to vacuum polarization.

A.3. Dimensional Folding: How Amplitude Is Actually Reduced

To understand amplitude reduction, imagine a stream of water striking a sponge:

- A small amount passes through the large channels (the α fraction).

- The rest is diverted into thousands of tiny capillaries.

In the τ-field, these “capillaries” are micro-curvatures and higher-order recursion folds. Rejected amplitude is not destroyed; it is folded into deeper recursion levels, where it becomes sub-structural noise.

If α were larger, the “capillaries” would widen and the Nest would leak — structure would dissolve. If α were smaller, the Nest would become opaque and Seeds could never interact. The observed value 1/137 lies exactly at the critical stability point.

A.4. The Moiré Filter Effect — Constructive vs. Destructive Echo Interference

Another perspective is to treat the boundary of the Nest as a recursive Moiré filter. When the internal self-echo overlaps with the external echo, the Φ-structured boundary produces a complex interference pattern.

Because the two recursions differ in origin, phase, and curvature, the interference is overwhelmingly destructive. Only the tiny fraction of geometric alignments that produce constructive interference contribute to the effective interaction we measure as the electromagnetic force.

α ≈ 1/137 = probability that an incoming echo finds a constructive alignment pathway.

Summary

The Nest does not resist; it misaligns. The τ-field does not absorb; it folds. Damping is not friction; it is recursive geometry.

The fine-structure constant α is therefore the probability that an external echo successfully solves the recursive maze on its first traversal of the Nest boundary. This is the UNNS geometric meaning of the most important number in electromagnetism.