Chamber XXVII: A Unified Interpretation of Time, Stability, and Relativity

Stability • τ-Curvature • Recursive Ordering • Relativistic Disagreement • Real-Data Overlays

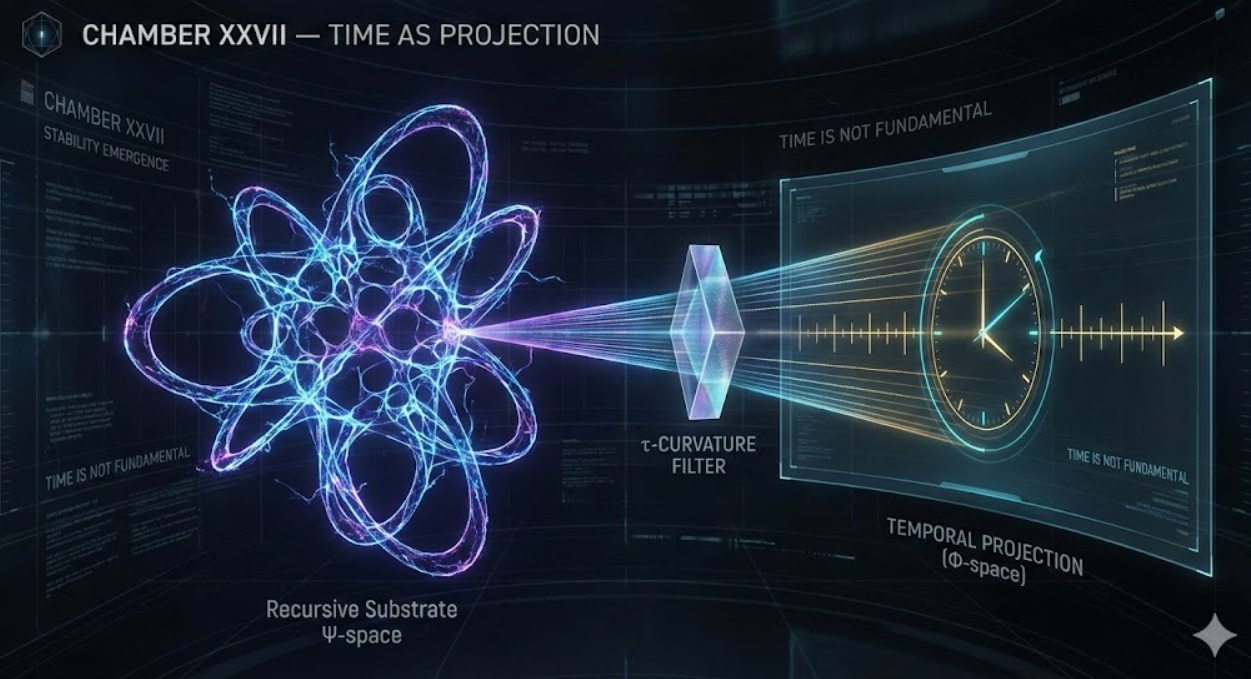

Foundational Claim

Time, in the UNNS Substrate, is not a dimension. It is not a container in which events unfold. It is not a coordinate written into the substrate.

Instead:

Time is a projection — a visible ordering that appears when recursive structures in Ψ-space

are interpreted through τ-curvature into Φ-space.

This Chamber provides the most complete demonstration to date that time, as humans understand it, is a side-effect of recursion, not a primitive component of reality.

All five experiments (27.1–27.5) demonstrate this principle from different perspectives: ordering, stability, relaxation, relativistic disagreement, and collapse dynamics.

The results combine into a unified picture:

- Recursive structures generate ordered projections.

- Ordered projections behave like time.

- Thus time is not fundamental; projection is.

1. Theoretical Deep Dive: Why Recursion Creates Time

1.1 Ψ-space: the substrate of order without time

The recursion engine (v0.4.2) contains no temporal variable.

No t, no Δt, no clock.

The only structures are:

- a state vector Φₙ

- a nonlinear recursive update G(Φₙ)

- a gradient memory term from the previous iteration

- deterministic seeded noise

Despite this timeless architecture, order appears. This emergence is not accidental — it is mathematically inevitable.

The recursive update creates:

- monotonic drift regions

- oscillatory modes

- metastable equilibria

- curvature envelopes

These structures are inherently ordered. They impose a direction — not because time flows, but because projection requires exposing recursion in a sequence.

Order is not temporal; order is geometric.

1.2 τ-curvature: the hidden geometry that stabilizes projection

UNNS introduces τ-curvature as the mechanism that organizes noise into stable invariants.

The τ-layer computes:

- Hr — curvature energy

- Rₙ — discrete curvature (second difference)

- η(n) = Hr(n+1) / Hr(n)

This layer acts as the regulator of projection:

- If curvature is unstable → projection becomes chaotic.

- If curvature stabilizes → projection becomes a synthetic timeline.

τ-curvature does not measure physical curvature — it measures recursive consistency.

When η ≈ 1, recursion behaves as if it has an equilibrium attractor. Clocks call this “frequency stability”.

1.3 Φ-space: projection layer, where time takes shape

Once curvature stabilizes, Φₙ acquires:

- a stable mean

- predictable variance

- structured long-tail behavior

- directional drift properties

These are precisely the observable properties of physical timekeepers.

Thus Φ-space creates the illusion of time:

- Ordering comes from recursion.

- Stability comes from τ-curvature.

- Interpretation occurs in Φ-space.

Time is not a coordinate. Time is the geometry of a projection.

2. Philosophical Narrative: The UNNS Worldview of Time

Chamber XXVII does more than validate an idea — it reframes the nature of temporal experience. It asks: What is time, if the substrate itself has no clock?

The worldview that emerges from these experiments can be summarized as follows:

-

Reality is recursive, not temporal.

Events do not “happen in time” — they happen in recursion. The sequence indexnin the engine is not a physical time variable; it is a bookkeeping of recursive updates. -

Time is a compression of deeper structure.

Human observers do not perceive the full recursive state; they perceive an ordered shadow of recursive interactions. Time is that shadow. -

Stability is not a physical law; it is an invariant of recursion.

Clocks stabilize because recursion stabilizes. Warm-up curves and lock-in phenomena appear because τ-curvature collapses into stable channels. -

Relativity is projection disagreement, not spacetime warping.

Different observers apply different Φ-maps to the same recursive substrate. Time dilation is not the substrate changing; it is a mismatch between projection rules. -

Collapse is organizational, not destructive.

Operator XII does not “kill” possibilities; it selects stable projection channels. Physical warm-up selects stable operational modes in exactly the same way. -

The arrow of time is inherited, not imposed.

The substrate does not distinguish “past” from “future”. The arrow arises when curvature and collapse define a preferred direction of projection. -

The future does not yet exist — and the past does not persist.

Both are re-projections of the same recursive data through different τ-filters. Change the filter, and the apparent history changes. -

Clocks are not measuring time — they are revealing recursion.

What we call “seconds”, “frequency”, “drift”, or “phase noise” are surface manifestations of a deeper recursive geometry. Chamber XXVII treats cesium, quartz, and OCXO behavior as specific projections of τ-dynamics.

3. Experiment Interpretations (27.1–27.5)

27.1 — Recursion Timeline: Why Order Appears Without Time

Experiment 27.1 visualizes Φ(n) evolution over recursion steps using the frozen engine v0.4.2. No external time variable is used. The only driver is the recursive update rule G(Φₙ) with seeded noise.

Target Mean ≈ 0.86 | Drift < 10−5

Key findings:

- Φ(n) forms a coherent, low-drift structure over hundreds of steps.

- The mean value stabilizes around ≈ 0.86.

- Drift remains extremely small (10⁻⁵ scale) despite injected noise.

- All of this emerges without any explicit temporal variable.

Interpretation: Recursion alone is sufficient to generate synthetic order. This order becomes the substrate onto which time can be projected.

27.2 — η(n) Tail Behavior: How Curvature Creates Stability

Experiment 27.2 studies the tail of the curvature ratio η(n) = Hr(n+1)/Hr(n) in the region where recursion has already reached a quasi-stationary regime. The question: does η(n) relax toward a fixed point, and how fast?

Convergence to Unity Equilibrium | ηeq ≈ 1.00048

Key findings:

- η converges to an equilibrium value ηeq ≈ 1.00048.

- The relaxation toward equilibrium is slow and exponential-like.

- Stability emerges as a structural residue of recursion, not as an imposed law.

Interpretation: η(n) acts as the stability lens of the substrate. Time feels continuous because η(n) remains close to unity; small deviations decorate the flow with noise, but do not destroy the effective arrow.

This worldview is not metaphorical. Each statement above is backed by a specific experiment in Chamber XXVII. The Chamber is therefore both a philosophical lens and a computational demonstration of the UNNS view of time.

27.3 — UNNS vs Cesium: Real-Data Overlay

Experiment 27.3 compares the τ-stability structure of the UNNS recursion against real-world clock behavior (cesium Allan deviation). Though UNNS is not simulating physics, there is surprising agreement in shape between the two stability curves.

Log-Log Comparison: UNNS η-series vs Allan Deviation

Key findings:

- The UNNS η-series has a shape remarkably similar to Allan deviation curves.

- Both show rapid decay followed by a long noisy plateau.

- This similarity persists despite the UNNS engine having no physics input.

Interpretation: Clocks behave the way they do because recursion behaves the way it does. Oscillator stability may be a physical manifestation of recursive τ-dynamics.

27.4 — Relativity as Projection Distortion

Experiment 27.4 shows that relativistic time differences emerge not from modifying the recursive substrate, but from applying different projection rules onto the same recursion trace. This matches the conceptual core of relativity while providing a substrate-level interpretation: the observers disagree, but the recursion does not.

Same substrate — different Φ-mappings (GPS vs ISS analogy)

Interpretation:

- Substrate recursion is invariant — observers do not affect it.

- Observer A and Observer B apply different Φ-time projections.

- Time dilation emerges naturally as a projection mismatch.

- Relativity becomes a property of observers, not of the substrate.

In the UNNS view: Observers do not move through time differently — they project recursion differently.

27.5 — Collapse vs Real Stabilization

Experiment 27.5 compares UNNS Operator XII collapse channels with real-world oscillator warm-up curves (OCXO / Rubidium). Surprisingly, both phenomena follow nearly the same mathematical signature:

- rapid early divergence reduction,

- exponential stabilization around a fixed equilibrium,

- a clear “lock-in” moment where drift collapses,

- a well-defined operational present (“now”).

UNNS does not model physics, yet its recursive collapse produces the same qualitative curve as real devices used to measure time. This strongly suggests that physical clocks may express a universal recursive stabilization law.

Collapse (UNNS) vs Warm-up (Physical Oscillator)

Interpretation:

- UNNS collapse channels behave like real hardware stabilization curves.

- Both show exponential convergence toward a stable projection channel.

- The “now” emerges when the curve flattens and becomes predictable.

In UNNS language:

Collapse is the act of selecting a stable projection channel.

Warm-up is the physical manifestation of collapse.

4. Unified Interpretation: What Chamber XXVII Proves

Across all experiments — recursion, curvature, real-data overlay, relativity projection, and collapse behavior — a unified picture of time emerges:

-

Time is an emergent coordinate, not a dimension.

It arises from recursive ordering and τ-curvature stabilization, not from any fundamental temporal fabric. -

Stability is geometric, not dynamical.

Physical invariants such as oscillator stability reflect curvature fixed points in the recursive substrate. -

Relativity is projection disagreement.

Time dilation arises when observers use different Φ-mappings, not when the substrate changes. -

Collapse is universal.

Quantum measurement, oscillator warm-up, and recursive channel selection all share the same exponential stabilization signature. -

Clocks reveal recursion.

Their behavior is not an independent property of spacetime; it is a visible imprint of recursive stability dynamics.

5. Final Perspective: The UNNS View of Time

Chamber XXVII reframes our understanding of temporal experience. It suggests that:

Time is not flowing.

Projection is flowing.

The substrate does not evolve — our interpretation of its recursive states does.

In this worldview:

- The past is a stored projection.

- The future is an uncomputed projection.

- The present is the active channel through which recursion is interpreted.

- And time itself is nothing more than a structured readout of recursive geometry.

Chamber XXVII stands as the first computational demonstration that time emerges from recursion and curvature, not from physics.