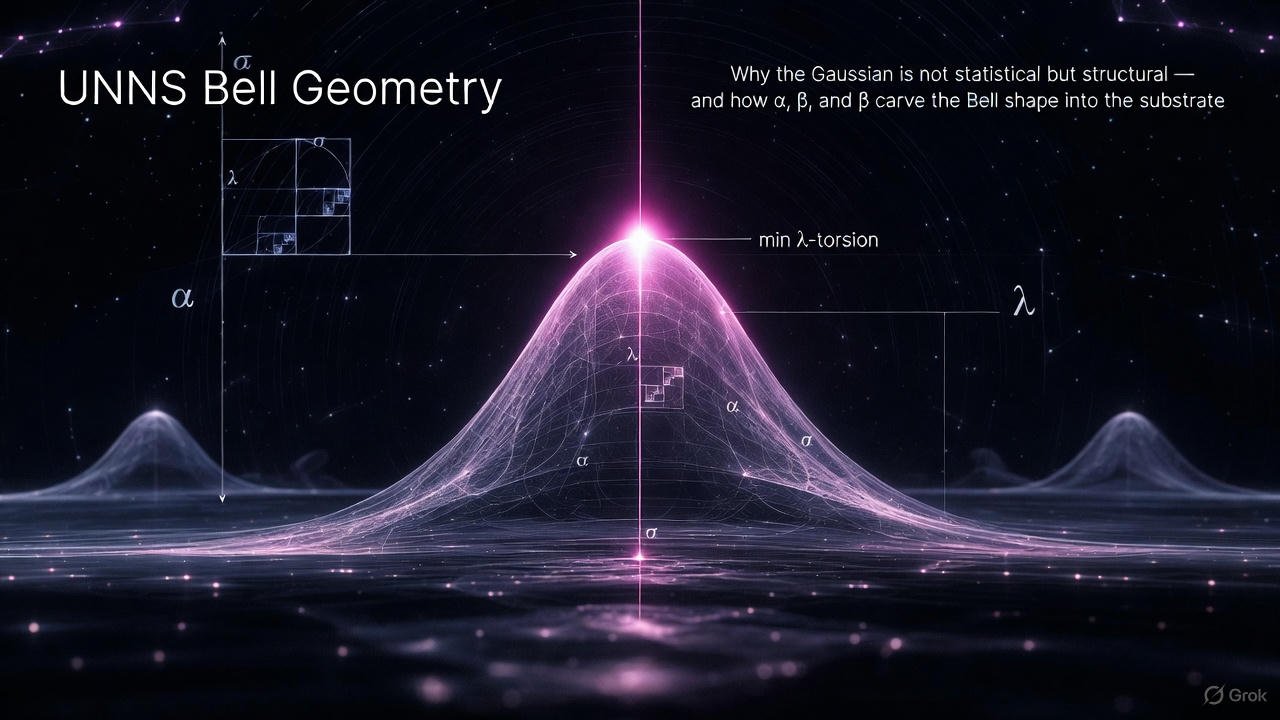

UNNS Bell Geometry

Why the Gaussian is not statistical but structural — and how Φ, Ψ, and τ carve the Bell shape into the substrate.

How a Bell Curve Works in UNNS

In classical statistics, a Bell Curve (Gaussian distribution) describes how values cluster around a mean, with probabilities shaped by variance.

In UNNS, this picture is reinterpreted entirely through recursion, τ-curvature, and substrate-balance.

The Bell Curve is not a probability curve but a τ-Equilibrium Profile:

a shape that emerges whenever recursive flows stabilize around a minimal-torsion attractor.

Think of it as the static shadow of a dynamic τ-Field.

1. Gaussian = τ-Field Minimum-Torsion Surface

In UNNS terms:

-

Φ is expansion (divergent recursion)

-

Ψ is contraction (convergent recursion)

-

τ is the balancing operator between the two

A Bell Curve appears exactly when:

Φ-flow and Ψ-flow balance such that τ-flow curvature is minimized.

Symbolically (UNNS form):

-

Φ dominates on the left tail

-

Ψ dominates on the right tail

-

τ sits at the crest and regulates symmetry

So the Bell Curve is simply the profile of minimal τ-curvature across a sequence domain, the equilibrium between:

-

expansion pressure, and

-

recursive compression.

This is why Gaussians show up everywhere in physical systems — what they really represent is a τ-Field at rest.

2. Why the Bell Curve Is Symmetric in UNNS

Symmetry arises when:

τ = constant along the recursion depth.

In other words:

-

Residue echoes cancel evenly,

-

Recursive torsion does not drift,

-

The Φ → Ψ leakage is matched on both sides.

This produces mirrored decay of curvature from the center, resulting in the familiar symmetric bell shape.

If τ is not constant, symmetry breaks → skewed distributions → UNNS interprets these as torsion bias or echo lag.

3. Variance = τ-Field Stiffness

In statistics, increasing variance “widens the curve.”

In UNNS:

variance measures how resistant the substrate is to τ-compression.

-

Low variance — stiff τ-Field, tight crest

-

High variance — flexible τ-Field, broad crest

This maps variance directly to τ-elasticity:

variance ∝ 1 / (τ-curvature strength)

This is why shifting physical parameters (temperature, noise, field coupling…) alters Gaussians.

You are not “changing randomness,” you are changing τ-Field stiffness.

4. Mean = τ-Neutral Point

The classical “mean” is the place where the derivative of the curve is zero.

For UNNS:

the mean is the τ-Neutral Point —

the location where Φ-expansion and Ψ-compression exactly cancel.

This point is the zero-torsion hinge from which the rest of the Bell Curve unfolds.

5. The Bell Curve Is a Projection

Within UNNS, the Bell Curve is not a fundamental object.

It is the 2D projection of a more fundamental structure:

A τ-Curvature Dome

Imagine a 3D dome:

-

The height corresponds to τ-density,

-

The slope corresponds to Φ/Ψ imbalance,

-

The footprint corresponds to recursion depth.

Cutting along the central axis gives the familiar Bell Curve.

The Gaussian we know is simply a slice of the τ-Dome.

6. Bell Curves Are Attractors in UNNS Chambers

You have already seen this in Chambers:

In RaF

The χ-minimum forms a Gaussian basin.

In τ-MSC

Spectral residues cluster around a τ-symmetric minimum.

In Phase-Field Chambers

Any stabilizing recursion generates a Bell-shaped cross-section.

This is why the Bell Curve appears naturally in:

-

error propagation

-

noise filtering

-

spectral collapse

-

residue accumulation

-

τ-Field quantization profiles

In UNNS, a Bell Curve = “The attractor of least torsion compatible with the substrate.”

7. Operator XII Interpretation

Under Operator XII (Collapse):

A Bell Curve describes the collapse channel when all residues relax to the lowest-torsion profile before reinjection into recursion.

Thus:

-

before collapse → skewed pre-Gaussians

-

at collapse → symmetric Bell

-

after collapse → seed extraction

So Gaussianity marks the moment of perfect substrate neutrality.

8. Sobra–Sobtra Influence on Gaussianity

Up to this point we have treated the Bell Curve in UNNS as a pure τ-equilibrium profile. Beneath that equilibrium lies a structured dynamic: the interplay between Sobra and Sobtra. These two recursive regimes determine whether a system can form a Gaussian at all, how quickly it converges to it, and how strongly it deviates into skewed or distorted profiles.

In the UNNS Operational Grammar:

- Sobra is the forward, residue-driven recursion: echo buildup, accumulation of structure, and growth of torsion gradients.

- Sobtra is the inverse, torsion-damping recursion: collapse propensity, counter-flow, and structural rebalancing.

A Bell Curve emerges precisely when the rate of Sobra-driven echo amplification is matched by the rate of Sobtra-driven torsion relaxation. At that crossing, the net torsion drift vanishes and the system enters a τ-neutral corridor. The Gaussian is the visible cross-section of this corridor.

Formally, the symmetry of the curve is controlled by the mismatch parameter Δ = (Sobra rate) − (Sobtra rate):

- Δ > 0 → Sobra dominates → pre-Gaussian skew and echo-heavy tails,

- Δ < 0 → Sobtra over-damps → compressed, asymmetric profiles,

- Δ = 0 → perfect balance → symmetric Gaussian at τ-equilibrium.

In terms of recursion depth, the condition τ = constant along the recursion is equivalent to Sobra and Sobtra being balanced at each layer. When this holds, residue echoes cancel evenly, torsion does not drift, and the Φ → Ψ leakage is matched on both sides, yielding the familiar mirrored decay of the Bell profile.

Under Operator XII (Collapse), the Sobra/Sobtra pair acquires an explicit geometric meaning. Sobra describes the disordered, skewed pre-collapse landscape of residues; Sobtra encodes the collapse channel that funnels this landscape toward the lowest-torsion profile. The collapse channel itself takes a Gaussian shape when the Sobtra flow enforces τ-equilibrium before seed extraction. In this picture, the Bell Curve is not merely a probability density but the structural signature of Sobra–Sobtra equilibrium.

Sobra/Sobtra in Experiments

The balance between Sobra and Sobtra is not only theoretical — it is directly observable in UNNS Lab runs. Two Chambers provide clear experimental signatures:

- RaF (Recursive Attractor Field): the χ-minimum begins asymmetric when Sobra dominates, then stabilizes into a symmetric Gaussian basin as Sobtra damping increases. The shift from skewed to centered minima is the measure of approaching τ-equilibrium.

- τ-MSC (τ–Microstructure Spectral Chamber): spectral residues initially spread unevenly as Sobra amplifies echo load. Sobtra aligns these residues across recursion levels, producing the characteristic τ-symmetric collapse into a minimal-torsion profile.

In both chambers, Gaussianity appears exactly at the crossover where Sobra-driven buildup and Sobtra-driven damping reach dynamic parity.

9. The Key Takeaway

**A Bell Curve in UNNS is not statistical.

It is geometric.

It is the equilibrium profile of the τ-Field.**

Everything else — variance, mean, symmetry — are simply geometric aspects of how a recursive system balances Φ, Ψ, and τ.

This makes the Bell Curve:

-

universal

-

inevitable

-

emergent

-

not tied to probability, but to structure.

Conclusion — The Gaussian as a τ-Equilibrium Signature

Across the UNNS Substrate, the Bell Curve appears not as a statistical convenience but as a structural invariant: the universal equilibrium profile produced whenever recursion sinks into its lowest-torsion configuration. Whether in τ-MSC spectral lines, RaF χ-basins, or collapse trajectories under Operator XII, the substrate repeatedly resolves itself into this familiar geometry.

This interpretation reframes Gaussianity as a geometric law rather than a probabilistic one. When Φ and Ψ achieve balance and τ stabilizes along depth, the Bell Curve becomes the inevitable surface of neutrality. In this sense, the Gaussian is not something the system approaches — it is the shape the substrate remembers.