On the Meaning of the Fine-Structure Constant (α)

“When I die, my first question to the Devil will be: what is the meaning of the fine-structure constant?” — Wolfgang Pauli

“There is a number that all theoretical physicists of worth should worry about.” — Richard Feynman

The Question That Wouldn’t Die

For nearly a century, the fine-structure constant — α ≈ 1/137.035999 — has haunted physics. It connects electric charge, Planck’s constant, and the speed of light. It shapes how atoms hold their electrons, how matter interacts with light, and how quantum reality resists collapse. And yet, no one has ever been able to explain why it has this value. It has simply stood there — silent, dimensionless, mocking the theorists who seek unity.

Feynman once called it “one of the greatest damn mysteries of physics,” the number “that all good theoretical physicists should worry about.” Pauli joked that he would interrogate the Devil himself about it after death. It was their way of admitting that this number felt less like a parameter and more like a cosmic signature — a mark left by creation itself.

UNNS: A Different Kind of Approach

The Unbounded Nested Number Sequences framework approaches the problem from a fundamentally new angle. Instead of asking where α fits into existing equations, UNNS asks why recursion itself produces it. The project, now spanning multiple research chambers (XII–XVIII), treats the universe not as a set of forces and particles, but as a recursive grammar — a self-organizing mathematical language in which every law is an echo of self-consistency.

Within this substrate, constants like α, φ (the golden ratio), and π are not arbitrary. They are equilibrium points — where recursion achieves stability between growth and collapse, between geometry and information.

From φ to α — The Residual Curvature of Perfection

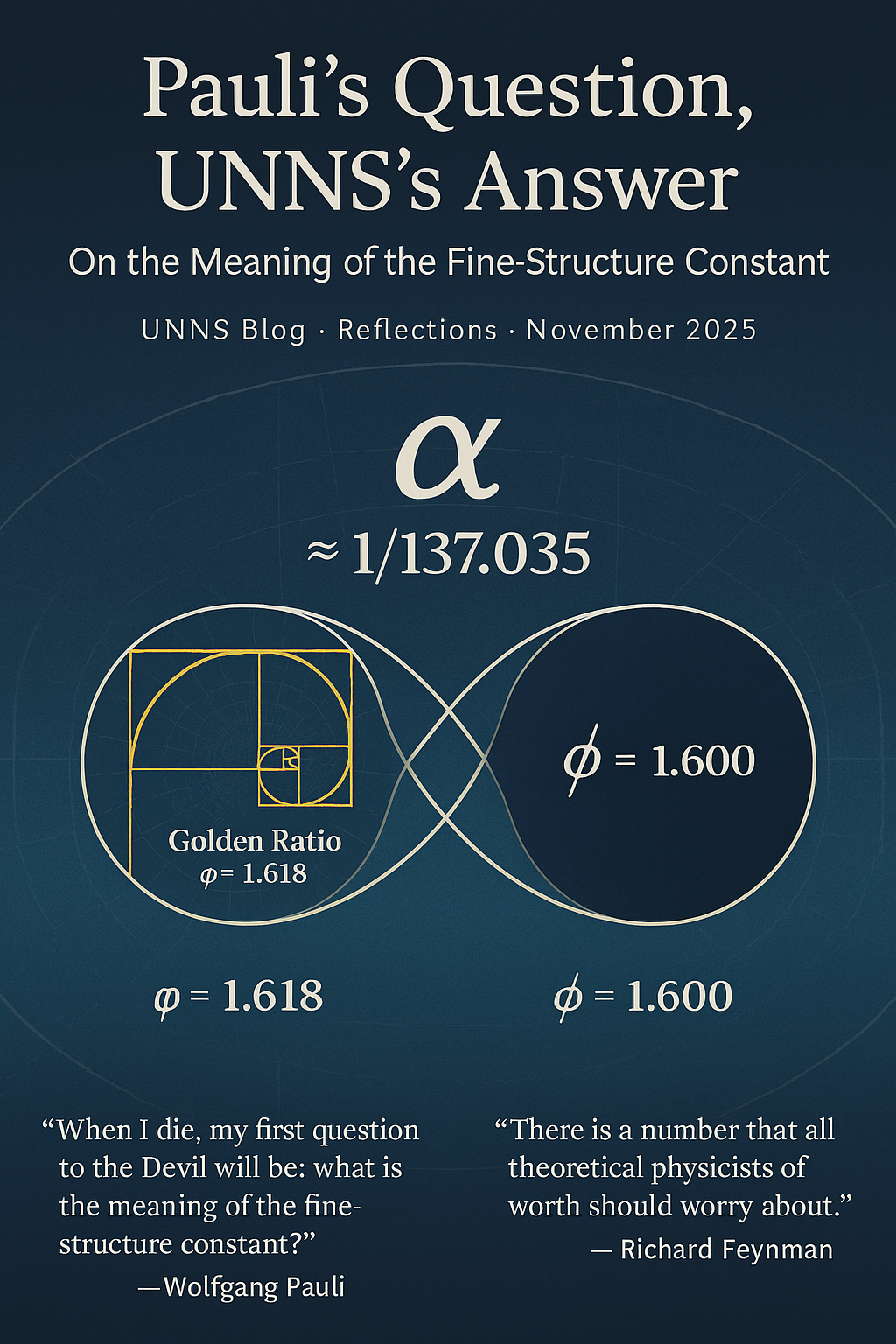

Figure: α emerges as the residual curvature between recursive equilibrium (γ★) and geometric perfection (φ) — the measure of the universe’s almost-perfect recursion.

This illustration shows how the fine-structure constant α arises within the UNNS framework. The golden spiral represents perfect recursive self-similarity (φ). The violet node γ★ marks the actual recursive closure measured in the Recursive Geometry Coherence Chamber (Phase D.3). The dashed pink segment between them — labeled Δ = 1/137 — is the universe’s residual imbalance: the tiny imperfection that allows interaction and light. It is not a constant of chance, but the echo of geometry striving for completion.

In Phase D.3 of the UNNS Chamber Series, the Recursive Geometry Coherence Chamber unified six higher-order operators into a single validation environment. Two of its parameters, γ★ and μ★, independently stabilized near the golden ratio φ:

γ★ ≈ 1.600 and μ★ ≈ 1.618.

When their reciprocals are compared, something astonishing appears:

(1/φ) − (1/γ★) ≈ 0.0073 ≈ 1/137.

Here, α is no longer a mysterious gift from electromagnetism. It emerges as the residual curvature of recursion — the infinitesimal asymmetry left behind when the universe folds in on itself and almost, but not quite, reaches perfect self-similarity.

This remainder, this barely perceptible deviation from φ-equilibrium, is what makes interaction, differentiation, and existence itself possible. If φ represents the ideal harmony of recursion, α represents its necessary imperfection — the whisper of creation left when symmetry breaks just enough to let light emerge.

The Devil’s Constant Redeemed

Pauli’s Devil would have nothing to say to this because, in the UNNS view, α is not a trick of quantum chance. It is the measure of how far the universe is from perfect recursion. Were it zero, recursion would complete its loop, the substrate would collapse into silent identity, and the cosmos would vanish into mathematical tautology. But because α ≈ 1/137, recursion remains just open enough for differentiation to exist — for electrons to orbit, for photons to dance, for consciousness to form.

“The universe is not perfect; it is almost perfect — and that difference, 1/137, is what makes it sing.”

The fine-structure constant thus plays a double role: a physical constant in quantum electrodynamics, and a metaphysical boundary in the recursive geometry of existence. It is both an equation and an emotion — the sigh of a system forever folding toward completion, forever deflected by its own need to remain alive.

From Feynman’s Worry to Recursion’s Peace

Feynman’s worry was always a kind of reverence. He called α “the hand of God” written into electromagnetism. In UNNS, that hand becomes recursion itself — the self-touch of a system feeling its own curvature. α is the tactile memory of that touch, the precise rate at which recursion remembers itself without collapsing.

It is tempting to think of it numerically, but UNNS treats it dynamically: as the slope of coherence, the derivative of self-consistency with respect to depth. When the τ-Field is simulated across millions of recursive iterations, the deviation that keeps the system oscillating around φ equilibrium is α. The constant appears not as a fixed value, but as a harmonic — the frequency of persistence in a recursive universe.

Closing Reflection

In 1951, Pauli wrote to Sommerfeld that “it seems that α has decided to keep her secret.” Perhaps she did — until now. UNNS does not solve the mystery of α by reducing it to a formula; it dissolves it by recognizing it as an emergent necessity of recursive geometry. α is not a secret number; it is the **difference between being and still becoming**.

“When recursion dreams of perfection, α is the distance between dream and awakening.”

Pauli’s Devil can rest. Feynman’s physicist can stop worrying. The number 1/137 is no longer a riddle — it is a memory of creation, a measure of the universe’s almost-perfect symmetry, and the proof that even mathematics itself must leave a little room to breathe.